I knew her as the art nun, but I also knew that she lived alone as a hermit. When I caught wind that a book was coming out about her (“Dearest Sister Wendy”, Robert Ellsberg) I was intrigued.

The book was not what I expected. I was expecting to enhance my appreciation of art, at least a little. Wasn't art the love of her life? But there is very little art commentary in this book, or spiritual insight into the art world.

Instead, there is personal honesty: a deep look at the inner world of an odd and holy woman who is called to a solitary life of prayer. And her miraculous opening out and sharing of herself in an almost daily correspondence with Robert Ellsberg during the last 2 years of her life.

It turns out that God is the love of Sister Wendy's life.

Sister Wendy is delightfully funny. And odd. And very smart. And humble. I'd almost say that she had no ego. Those 7 hours of daily praying must have been at a high order of meditation. And yet, in so many words, without words, she lets you know about this simple prayer of hers.

I’ve been intrigued with solitary monastic life for awhile, most of my life. When I was a child it was the Carmelite monastery in Louisville that most caught my attention. What did the nuns do in that walled and silent place? I’m odd, too - introverted - so I sort of can identify with and understand Sister Wendy.

Sister Wendy knew her way early in life. She joined an order of teaching nuns when she was just 16 years old. She never doubted this move or looked back. She followed the rules; she obeyed. Her life was totally in the hands of God and she trusted that the circumstances of life would guide her to where God wanted her to be. And they did.

After about 20 years in a teaching role Sister Wendy had a physical breakdown of sorts. Seizures that were diagnosed as epilepsy. She was given permission to live as a consecrated virgin and hermit. Secluded in a trailer on the grounds of a Carmelite monastery in Quidenham, England, Sister Wendy lived her life alone and in prayer. She went to the monastery for Mass every day, but otherwise she was in her little trailer, praying for at least 7 hours a day. She read - about art, about religion, about Thomas Merton, Pope Francis, and others.

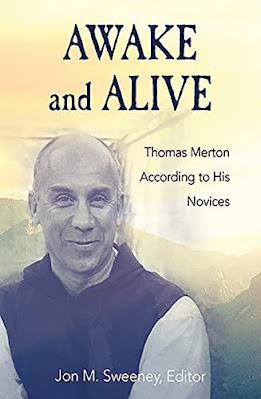

Sister Wendy took the rules of monasticism seriously, which is probably one of the reasons she had such a hard time with Merton. Merton talked a lot about the monastic life, but he broke most of the rules. His engagement with “the world” was relentless. She wondered why his writing did not convey much joy in his life.

Reading Sister Wendy’s takes on Merton is revealing. Even at 88 years old and in failing health, her mind is still sharp and penetrating. Her insights in to what is happening in the world are compassionate and wise. Most of her life has been spent in silent prayer, away from the world. Not talking to people. When her correspondence with Mr. Ellsberg begins, Sister Wendy is hesitant. How does one speak of a life of silent prayer? There are no words. Nothing, as she would say.

And yet, over the course of 2 years and possibly for the first time in her life, Sister Wendy relates from a deep and authentic place in herself who she is and who God is for her.